LeetCode 1559. Detect Cycles in 2D Grid

1559. Detect Cycles in 2D Grid

Given a 2D array of characters grid of size m x n, you need to find if there exists any cycle consisting of the same value in grid.

A cycle is a path of length 4 or more in the grid that starts and ends at the same cell. From a given cell, you can move to one of the cells adjacent to it - in one of the four directions (up, down, left, or right), if it has the same value of the current cell.

Also, you cannot move to the cell that you visited in your last move. For example, the cycle (1, 1) -> (1, 2) -> (1, 1) is invalid because from (1, 2) we visited (1, 1) which was the last visited cell.

Return true if any cycle of the same value exists in grid, otherwise, return false.

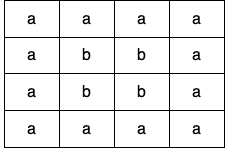

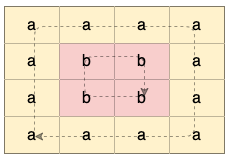

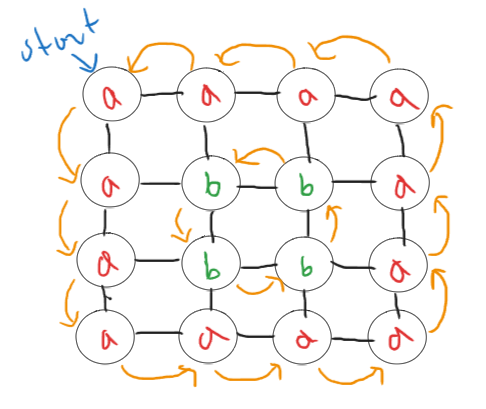

Example 1:

Input: grid = [[“a”,”a”,”a”,”a”],[“a”,”b”,”b”,”a”],[“a”,”b”,”b”,”a”],[“a”,”a”,”a”,”a”]]

Output: true

Explanation: There are two valid cycles shown in different colors in the image below:

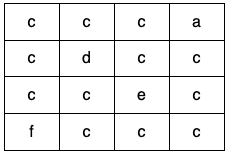

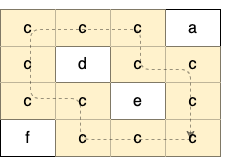

Example 2:

Input: grid = [[“c”,”c”,”c”,”a”],[“c”,”d”,”c”,”c”],[“c”,”c”,”e”,”c”],[“f”,”c”,”c”,”c”]]

Output: true

Explanation: There is only one valid cycle highlighted in the image below:

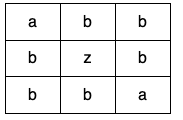

Example 3:

Input: grid = [[“a”,”b”,”b”],[“b”,”z”,”b”],[“b”,”b”,”a”]]

Output: false

Explanation: There is no cycle in the grid with the same value

A simple problem

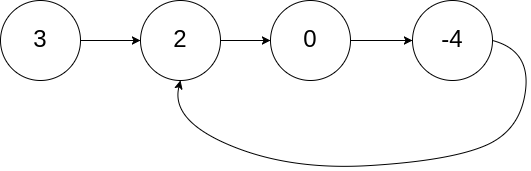

Before we solve this problem, let’s look at another LeetCode problem that bears similarty to this problem. The problem is LeetCode 141. Linked List Cycle.

Although Linked List Cycle problem is comparably easier than this problem, we can still gain some insight from Linked List Cycle.

In that problem, we are asked to check if there is a cycle in the linked list. There exists a cycle if there is a node that can be reached again by continuously following the next pointer of nodes.

Let’s see an example of that problem. Below is given a linked list with a cycle.

We start at the first node, which is often referred to as head of the linked list. We start following the next pointer of each node. Once we reach the node with value -4 (the node at the end, although it is not quite an end), the next pointer of this node, it will take us back to the second node,which we have already visited.

How do we solve this problem?

There are a few ways to solve it. Arguably the easiest one is to keep track of which nodes we have already visited and when we visit a node, check if it has already been visited.

So we can start traversing the linked list and remember the nodes we visit. As soon as we find a node that we have already visited, we can say that there is a cycle in the linked list.

We can now adapt this idea to our original problem.

Solution

In case of the Linked List Cycle problem, we could go in only one direction - forward by following the next pointer. In our case, this is a little different. Since we are traversing in a 2D array, we have four directions as it is mentioned in the problem description. We can go up, down, left and right if doing so does not take us out of the grid.

We will keep track of the cells we visit, and once we see a cell that has already been visited, we can stop the process.

All of the values in the cycle have to be the same. Let’s say we are at a cell with value c and want to go down one cell. If that cell does not have the value c, we can’t go to that cell as it does not belong to the path we are following. So, we only go to the cells with the same value as the cell we are currently at. If there are no cells that we can go to, we return false. We repeat this process from every unvisited cell.

Let’s first see how we can traverse a grid. We can traverse a grid (or somtimes called matrix) row by row. We can simply do this with nested for loops. However, that is not what we want in this problem.

We can view the grid as a graph. For example, let’s see the grid from example 1.

We start at the node on the top-left corner. We go down one node as it has the same value as the current node. And go again and again. We reach the bottom-left node, now we go one node to the right. Again this node has the same value. We keep going like this as far as we can go. We finally cycle around and reach the node we started at. So we found a cycle. There is actually another cycle. We can start at one of the nodes with value b (in green). That would be another cycle.

How did we know that we found a cycle?

We knew that because we kept track of all the nodes we visited. Once we reached a node that had been already visited, we concluded that we found a cycle.

Is there anything wrong with this idea?

Let’s see another example.

In the above example, you can see that we start at the top-left node again. We go down a node and we go down one node again. Now we can’t go down or left as there are no nodes (outside of grid). We can only one node up or to the right. We can’t go to the right node becaues it does not have the same value as the current node. So the only option is to go up one node, which has the same value as the current node. But if we go up, we go back to the node we just came from. Now since this code has been visited, we conclude that we found a cycle, which is a false alarm. That is not a cycle. First of all, the problem states that a cycle has a length of 4 or more. We have only 3 nodes in this path. Secondly, this path does not even end at where we started. That means it does not form a cycle. So you might be thinking “Okay, let’s not visit the nodes we have already visited”. But then how could we find out that we have a cycle. Because our idea is based on the fact that once we see a visited cell or node, we stop as this forms a cycle.

In fact, you are almost right. Let’s not visite the nodes we have visited. But that does not apply to every node. We will not visit only the immediate node we came from. In other words, we do not go back. For example, if you came to the current cell from one cell up, then your only options are down, left or right cells. You can’t go back to the above node. If you can’t neither down nor left nor right, we stop traversing, reasing that we couldn’t find a cycle. In case of linked list problem, we didn’t actually have this issue. Because we only traversed forward. Only node that took us back was the node that formed the cycle.

Let’s look at the code.

Code

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

#define vv std::vector

vv<vv<int>> dirs = { {1, 0}, {0, 1}, {-1, 0}, {0, -1} }; // this shows directions

//For example row = 1, column = 1. row = row + dirs[0][0] = 1 + 1 = 2

//column = column + dirs[0][1] = 1 + 0 = 1. Effectively, this takes us one row down

static int speedup = []() {std::ios_base::sync_with_stdio(false); std::cin.tie(NULL); return 1;}();

class Solution {

public:

bool containsCycle(vector<vector<char>>& grid) {

int n = int(grid.size());

int m = int(grid[0].size());

vv<vv<bool>> visited(n, vv<bool>(m)); //where we keep track of visited nodes

for(int i = 0; i < n; i++)

{

for(int j = 0; j < m; j++)

{

//we start every unvisited node

if(!visited[i][j])

{

//if found cycle, return true

if(dfs(grid, i, j, visited, -1, -1)) return true;

}

}

}

return false;

}

private:

bool dfs(vv<vv<char>>& g, int row, int col, vv<vv<bool>>& visited, int prevRow, int prevCol)

{

//if already visited, that is a cycle!

if(visited[row][col]) return true;

char ch = g[row][col]; // the current value of the cell

visited[row][col] = true; // visited

//go in all 4 directions (if possible) except for the cell we came from

for(const auto& d : dirs)

{

int r = row + d[0];

int c = col + d[1];

if(r < 0 || c < 0 || r >= int(g.size()) || c >= int(g[0].size()) || g[r][c] != ch ||

(r == prevRow && c == prevCol))

continue;

//if found cycle from this exploration, return true

if(dfs(g, r, c, visited, row, col)) return true;

}

//no cycle found, return false

return false;

}

};

Here the function dfs is the Depth-First Search traversal - a recursive way of traversing a graph (or graph-like structures such as grid in this problem). It keeps following a path as long as possible. Or as deep as possible. That is, in a way, why it is called Depth-First Search. First we go a path all the way to its depth and once we hit the end, we backtrack to a previous node and if available, follow another path from there as long as possible. The end might be defined differently for different problems. In this case we keep on exploring the grid as long as we are in boundries of the grid and we don’t reach a node with a different value from the value of current cell. Depth-First Search is a versatile traversing algorithm that can be more than just a traversing algorithm. For different problems, it can be modified to solve them. There is also a counterpart of Depth-First Search algorithm. It is Breadth-First Search traversal algorithm, which also has a lot of use cases although a little different than Depth-First Search. There are many problems out there that can be solved both by DFS and BFS and some problems can only be solved either DFS or BFS. DFS is usually implemented recursively, especially in cases where there is a lot to keep track of. In recursive implmentation, the function call stack takes care of all those. The iterative version of DFS uses a explicit stack data structure to remember the nodes to visit later. BFS is implemented iteratively by using a queue data structure. BFS, contrary to DFS, traverses a graph layer by layer. It traverses a layer completely before it moves on to the next layer. It traverses all the nodes that are one edge away from the current node. And then it traverses all the nodes that are two edges away from the current node, or in other words, all the nodes that are one edge away from the nodes that are one edge away from the current node.

I will consider covering basic algorithms and data structures in the future if there will be a need for that.

I hope you enjoyed this article. Come back for more!